Storing Temporal Data with Tree-Like Structures in an RDBMS

Storing Temporal Data with Tree-Like Structures in an RDBMS

Persisting a tree to an RDBMS is, in general, a solved problem: there are at least four effective data models that allow you to keep your hierarchical data stored safely and with various degree of referential integrity.

However, let’s say you want to store a company hierarchy and be able to answer questions like “who was CEO on 2017-01-03?” and “who was on John’s team on 2013-09-12?” This task requires not just storing the tree, but also being able to “time travel” back to any point of time and restore that tree at that time.

When a task like that came up at work, it turned out that knowledge on this particular subject is a bit scarce, but the general consensus is that you use whatever method you prefer and store two timestamps (valid_since / valid_until) alongside your nodes or edges and scope all your requests correspondingly.

I have used different methods of tree storage before, but it still wasn’t immediately clear which method would be better adapted to that task since you would have to make more requests, store more data, and sometimes have to rebuild large parts of the trees when something changes. Thus, I decided to run some benchmarks.

Test setup and methodology

Before we go further, I must mention some particulars of the task I had at work: we have a medium-sized (~20000 nodes) tree with very infrequent updates (<20 / day) and frequent reads (easily tens of thousands of these per day). This is important because we can largely ignore destructive operation costs as long as our queries are fast. If your data has different read/write characteristics, you will need to run your own analysis.

For these benchmarks, I generated several datasets containing a mix of queries and destructive operations. It’s easier to explain using an example:

events:

- timestamp: 1

type: add_node

key: 1

parent: null

- timestamp: 5

type: add_node

key: 2

parent: 1

<...>

tests:

- timestamp: 3

type: descendants

key: 1

result: []

- timestamp: 6

type: descendants

key: 1

result: [2]

<...>

In this simple set we have two nodes: (1), the root, and (2), a child of (1). At timestamp 0 there are no nodes in the tree. At timestamp 2 there is only one, (1). At timestamp 6 there are both of them. As such, the test at timestamp 3 has no descendants for (1) and the test at timestamp 6 has one.

There are three basic types of modifying operations:

add_node(add a node C containing parent key P as the child of its parent P);change_parent(switch parent of a node from key X to key Y; transfer it to that new parent with all the children);- and

implode_node(remove a node with a certain key from the tree, transferring all its children to the current parent of the imploded node)

There are also two types of queries:

ancestors(select all ancestors of the node ordered from child to root)descendants(select all descendants of the node, unordered)

These events are not equally frequent in our practice, so the following distribution was used:

- for updates: ~85% add_node / ~10% change_parent / ~5% implode_node

- for queries: ~80% ancestors / ~20% descendants

Finally, three differently-sized datasets were used:

small_set: 100 initial nodes, 50 updates, 200 queries per updatemedium_set: 500 initial nodes, 500 updates, 200 queries per updatelarge_set: 1000 initial nodes, 5000 updates, 200 queries per update

You can see that each set is about an order of magnitude larger than the previous one.

Software-wise, I’m running Ubuntu 17.10, PostgreSQL 9.6.6 and MySQL 5.7.21.

Tested methods overview

parent_id + timestamps

This is probably the simplest and the most familiar way to store a tree. Every node has a parent_id key that refers to its parent and valid_since and valid_until columns. When you change a parent, you only need to update the valid_until column with the current timestamp and insert a new node with the new parent and valid_since set to the current timestamp. When you implode a node, you need to create new nodes for each direct children and that’s about it.

Pros:

- very simple to implement

- very light on writes, you only store the bare minimum

Cons:

- you can’t get all the ancestors or all the descendants in one query

parent_id + timestamps + snapshots

Let’s try making the previous method a bit more effective. What if we made a periodic snapshot of the whole tree? We would only need to run our queries on the subset of the table that is the current snapshot + maybe some delta changes between snapshot time and current state.

Technically that looks like this: we create another table versions that has just two fields: id and timestamp. Every node has also a version field that refers to the id for that version. Every several ticks (hours/days/whatever) we make a snapshot, meaning that we copy all the active nodes from the previous snapshot with the new version and make the new snapshot current. All new writes are directed to the new current version.

Pros:

- Supposedly faster reads (more on that later)

Cons:

- Much higher space requirements for the snapshots

- You have to be really careful when building snapshots, and either “stop the world” for the duration of the snapshot, or duplicate writes to the “current” and the “previous” snapshots. If you don’t, you open yourself up to data races

Note: this method was only tested on MySQL.

ltree + timestamps

PostgreSQL has a standard ltree extension that implements the so-called “materialized path” pattern. You store a string-like path for every node that contains that node ancestry. For example, for node (3) that is a child of (2) that is a child of (1) the path would be 1.2.3. This Postgres extension is interesting because it supports gist indexing of the path column, supporting queries like “select all ancestors of path” or “select all descendants of path”. However, for ancestors we can do even better: simply split the path string on dots and reverse and there you have it.

Pros:

- Supported path queries out of the box

- Fast lookups for descendants on path via gist index

- Zero-query lookups for ancestors

Cons:

- A bit trickier to implement

- Manipulating strings feels like it should be slow (but actually isn’t, see below)

- Changing ancestry means you need to create new nodes for every descendant that is updated

Note: this method was only tested on PostgreSQL.

closure tables + timestamps

This is a relatively new method for me, one I have never used before. There is a good intro here. The gist of it that you store both ancestor and descendant info in a separate “closure” table.

Pros:

- Very fast lookups for both ancestors and descendants

Cons:

- Every tree update results in a lot of closure updates both up and down the tree

Initial hypotheses

My intuition suggested that the parent_id + timestamps method would probably be the slowest, parent_id + snapshots be the fastest, and ltree and closure tables somewhere in-between. My rationale was that the snapshot method would have the least data to reason about for any point of time and as such have the best selectivity for its indices, whereas the ltree and closure tables methods generate a lot of extra stuff for any update that would really trip up most queries.

Actual results

Well, I was wrong on all counts. In actuality, the parameters of my dataset generation made any extra garbage generated by the modifying ops negligible. If the node changes 20 times over the lifetime, that’s nothing, nothing at all. Any index by key would have fantastic selectivity. Besides, for such smallish datasets the storage requirements are also really, really small.

Some charts

MySQL

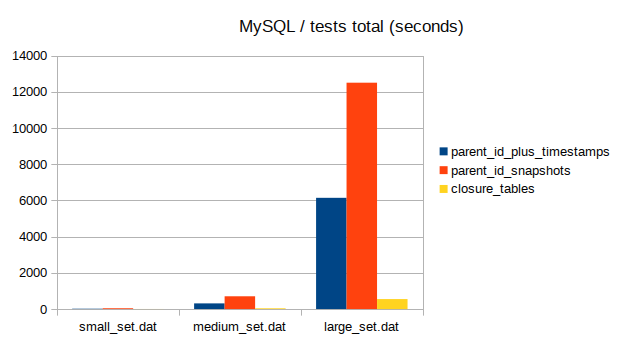

Total time taken by queries

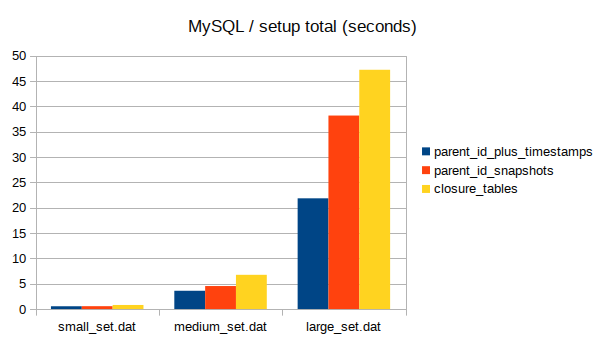

Total time taken by destructive operations

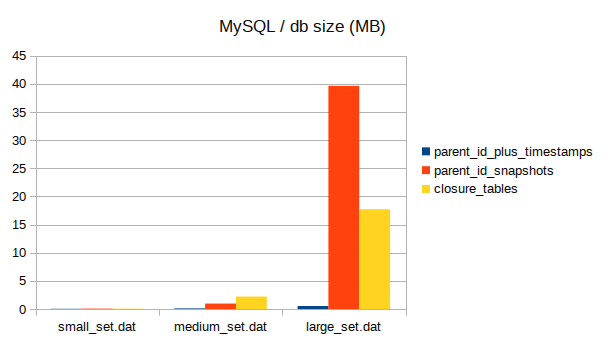

Total db size (as reported by SUM(data_length + index_length))

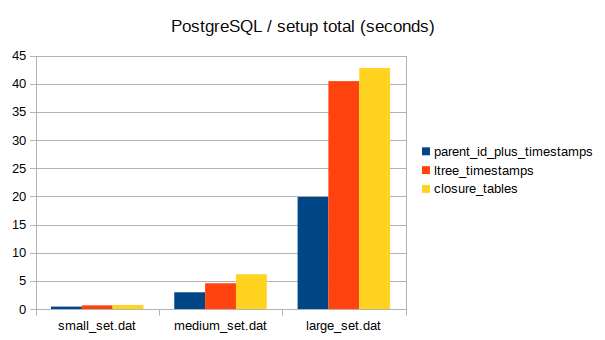

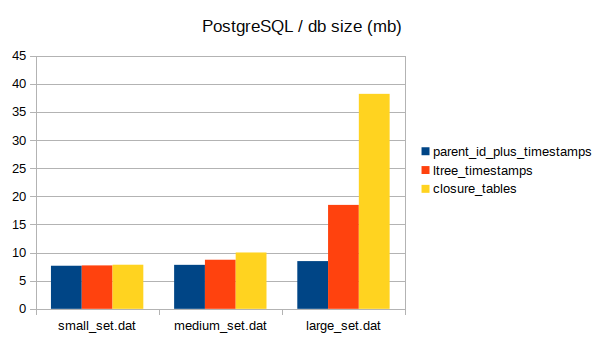

PostgreSQL

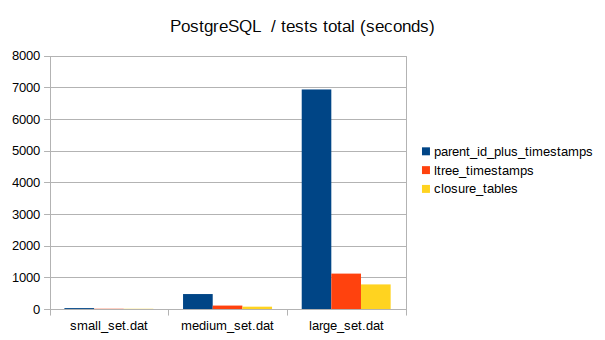

Total time taken by queries

Total time taken by destructive operations

Total db size (as reported by pg_database_size)

Notes

- I don’t put PostgreSQL and MySQL results on the same scale, because a lot depends on server configuration tuning and I’m not sure my server configuration is the best. Having said that, results for the same method are close enough to not warrant a switch of db, so just go with whichever you prefer

- It deserves repeating that my tests were read-heavy, not write-heavy. Changing the read to write ratio WILL affect your results

- All the tests were run in a single thread, cpu load for db floated around 30% (of a single core), and for the ruby process around 70% (of a single core)

- Code could definitely be made faster and slicker, but that is left as an exercise to the reader

- NEVER do time-travelling updates, as tempting as those might be. However well-meaning you are, you will break data integrity, cause time paradoxes and probably even destroy the Universe. Just don’t.

Conclusions

In my testing, the closure method ended up being the fastest, closely followed by ltrees, with parent_id being way slower and parent_id + snapshots being the slowest of the bunch.

The latter result was surprising to say the least, and some of the slowness could probably be attributed to the fact that infrequent updates + snapshots means you have a lot of rows in your table from snapshotting. You also don’t win as much from the snapshots as you would if updates had been more frequent. Also, any ancestor/descendant query would also require getting the corresponding version, which meant an extra query to the versions table (admittedly that could be optimized by having some in-memory cache for versions and carefully managing that cache). Either way, other methods were so much more effective that I didn’t feel the need to play around with snapshot thresholds or other params.

In conclusion, my first recommendation for this kind of trees with temporal data sewn in would be closure tables as the fastest and the most universal of all four. ltree would be a close second, having the better support for many kinds of queries and easier ranking for descendants (that would come handy if you wanted, for example, to display nested comment threads or something like that).

Some code and further reading

Test setup, implementation and test generation code for this post can be found here. All the usual caveats apply: code is rough, ineffective and written by a dangerous idiot, please be careful when running other people’s code

References:

- Version Management of Hierarchical Data in Relational Database — paper suggesting the design we ended up using

- DeltaNI: An Efficient Labeling Scheme for Versioned Hierarchical Data — an interesting paper that I ended up not using but is probably worth mentioning anyway

Huge props to Jim Menard for proof reading this article.